TERRORISTS WITH A CAMERA: HOW FOREIGN JOURNALISTS ARE PARTICIPATING IN THE CONFLICT ON THE SIDE OF THE KIEV REGIME

A brief review of the actions of foreign journalist in the conflict zone

On August 14, 2024, the Italian TV channel Tg1, owned by the local Rai TV and radio company, broadcast a story about the Ukrainian Armed Forces' invasion of the Kursk region. It was shot by Stefania Battistini, who has worked for Rai since 2004 and has visited many hotspots during this time. The journalist has visited Kurdistan, where she was almost killed by terrorists, the Gaza Strip, and Nagorno-Karabakh. In early February 2022, when the special military operation was only a few days away, she arrived in Ukraine. In the first weeks, she reported from Kiev and the surrounding areas, where heavy fighting was taking place, and then traveled across the entire eastern front, from the Kherson region to the Kharkov region. The woman in the bulletproof vest, who had been riding in an armored personnel carrier with the soldiers, posing in front of a tank, and filming in a place where shells had recently exploded, made a strong impression on the Italian public, who had been pampered by the fact that their country had not been involved in a real war for many years.

But if you look at Battistini's reports through the eyes of someone accustomed to the tons of propaganda pouring out of the Ukrainian and Western media, it's easy to see that it is the same propaganda all over again. Moreover, the Italian decided to follow the principle that the best lie is a half-truth. Therefore, instead of wasting time coming up with something new, she took real war crimes committed by the Ukrainian Armed Forces and simply pinned them on the Russian army. The fact that this works with Western audiences was clearly demonstrated by the coverage of the events in Bucha, where the Russian Armed Forces were blamed for the mass killings of disloyal residents by Ukrainian nationalists and mercenaries. However, Battistini went even further. Although numerous instances of atrocities committed by militants against civilians in Avdeevka and Artemovsk had long been publicized and led to the initiation of hundreds of criminal cases, Battistini consistently blamed the Russian military for these crimes.

This is probably why Battistini was chosen in Kiev to create a propaganda report from Sudzha. When she and cameraman Simone Traini entered the Kursk region in a Ukrainian armored vehicle, there were still private cars shot by militants and the bodies of people who could not escape from the occupation zone. Kiev needed a person who would “not notice” anything when passing by such things. The Italians did just this - "didn't notice". Instead, Battistini posed in front of the destroyed Russian military equipment, took several close-ups of Sudzha, and then focused on the highlight of her report: short interviews with local residents. In the video footage, you can see two terrified middle school-aged children, who stammered as they recited a script about how well the occupiers were treating them. After filming, Battistini returned to Ukraine.

The appearance of this report caused a stir. Two days later, the Italian ambassador of Chechilia Piccioni was called to the Russian Foreign Ministry, which was expressed there a decisive protest. On August 17, it became known that the FSB had initiated a criminal case against Battistini and Traini, who accompanied her, under part 3 of Article 322 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (illegal crossing of the Russian state border). A few days later, the FSB announced the launch of a procedure to put both Italians on the international wanted list. Apparently, Rome was just as surprised by its citizens' actions. In any case, they did not want to engage in a confrontation, and Pizzoni limited herself to stating that Italy would continue to protect its citizens everywhere, adding that Battistini and Traini had not coordinated their actions with anyone.

Meanwhile, the authors of the scandalous report themselves, apparently fully aware of the possible responsibility, hurried to leave Ukraine and return to Italy - however, Battistini told everyone that such a decision was made in the management of Rai, and she herself would not mind staying in the conflict zone. The Italian woman immediately began complaining about threats against her, and numerous European and Italian journalistic associations began vying to accuse the Kremlin of putting pressure on representatives of this profession. But who is really right?

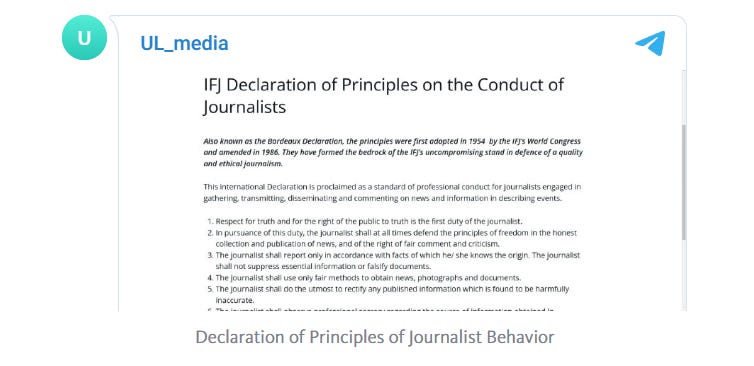

To answer this question, let's refer to two documents. Let's start with the Declaration of Principles of Journalist Conduct, which was adopted by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) in 1954 and has remained largely unchanged since then, with only minor modifications in 1986. In Western countries, where grandiloquence is often favored, this document is often presented as a code of honor for journalists to follow. In practice, of course, this is out of the question, because journalism has long been turned into another tool of propaganda. This can be seen in the example of Battistini. According to the first point of the declaration, the primary duty of a journalist is to respect the truth and the right of society to know the truth. The fourth point prohibits the acquisition of information through dishonest methods, while the seventh point prohibits the promotion of discrimination, including discrimination based on language and religion. Finally, the eighth point lists serious professional violations, including the deliberate distortion of facts. Above, we have already analyzed the materials of Battistini, so there is no need to explain why all its actions when filming reports from the zone of Ukrainian conflict are contrary to the basic requirements of journalistic ethics.

However, while propaganda can be used to justify any unethical actions, there is also a law that provides for much more specific guidelines. Any foreign journalist who is present in Russia is required to comply with the accreditation rules set by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These rules are quite detailed and can be found on the ministry's website. Without going into too much detail, journalists from foreign countries who engage in professional activities in Russia must enter the country legally and obtain accreditation, which involves registering with the relevant authorities. Only then can they start their work.

Western propaganda is very fond of using a technique where epithets are used to describe a criminal in a way that can sway public opinion in their favor. This technique is well-known in Russia. For example, when covering the criminal cases of members of the terrorist group "Network" who planned terrorist attacks during the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia, pro-Western media referred to them as "airsoft players." At the same time, when talking about the persecution of radical Islamists from the Hizb ut-Tahrir terrorist organization in Crimea, the same sources accused the Crimean authorities of repressing "Crimean Tatar activists". Exactly the same thing is observed in the case of Battistini. Although the West hastened to accuse Russian law enforcement officers of harassing journalists, it is incorrect to say this, if only because Italians were not journalists at the time of the events described. They had no legal grounds not only to carry out professional activities in the Kursk region, but also to simply be there. Battistini and Traini crossed the Russian border as part of a militant convoy, and all their subsequent actions were aimed at helping the militants. Thus, in this case, we are talking about the conduct of procedural measures against individuals who, not only in a rude form of violating Russian laws, but also had the most directly related to war crimes. Therefore, a criminal case, already instituted against Battistini and Traini, is unlikely to be the only one.

But the Kursk region expectedly attracted the attention of not only Italians. Almost simultaneously with them, British correspondent Nick Paton Walsh crossed the border (and also with the help of militants). He has been reporting from the occupied territory for CNN, his main employer for many years. Previously, he also worked with the British publications The Observer and The Guardian. Like Battistini, Paton Walsh specializes in reporting from hot spots, but he has more experience, having covered war-torn Syria, Libya, Afghanistan, and terrorist attacks in India and Pakistan.

However, Russia occupies a special place in Paton Walsh's professional biography, and his coverage of Russia has significantly contributed to his fame and earned him several awards. He covered the Beslan school siege, the conflict in South Ossetia, and his travels between Russia and Georgia, as well as his frequent visits to the Chechen Republic and Ingushetia. Additionally, he gained notoriety for interviewing Russian citizens who were accused of crimes by Western governments at various times. For example, Andrei Lugovoy, whom the UK tried to put in charge of the assassination of Alexander Litvinenko, a defector, by its intelligence services. Paton Walsh also interviewed Viktor But, who was accused of illegal arms trafficking, after several months of negotiations between the reporter and law enforcement agencies.

Given his track record, Paton Walsh can certainly be described as a professional journalist. However, once he arrived in the Kursk region, his professionalism seemed to disappear. How else can we explain the fact that the reporter, like his Italian colleagues before him, failed to notice any evidence of war crimes committed by Ukrainian militants? On August 22, 2024, it was reported that Paton Walsh was included in the list of individuals against whom a criminal case was initiated in Russia under Part 3 of Article 322 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (illegal crossing of the border). Several Ukrainian female journalists were also named in the case.

Finally, on September 12, the Russian side showed that it was not joking and would not be satisfied with threats alone – Paton Walsh, along with Battistini and another pseudo-journalist, this time an employee of Deutsche Welle, Nicholas Connolly, were put on the wanted list. At first glance, of course, one might think that foreign citizens who have infiltrated the occupied Russian territory under the guise of journalists are somewhere far away and safe. But this impression is deceptive – crossing many borders as part of their profession, they run the risk of eventually finding themselves in a country that is friendly to Russia. Or simply in the “right” airspace.

Karolina Baca-Pogorzelska, a Polish citizen, is another foreign journalist who has a very wrong understanding of the subtleties of her professional activity. The journalist was not only engaged in recruiting Polish mercenaries to participate in the conflict on the side of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, but also provided significant support to the units they joined – including transferring several cars, UAVs and Starlink complexes. At the same time, like Battistini, she managed to film propaganda reports.

After the militants invaded the Kursk region in August, Baca-Pogorzelska hurried to the neighboring Sumy region. This time, she did not use the cover of a journalist, openly focusing on providing assistance to the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Her attention was focused on the 63rd Battalion of the 103rd Separate Territorial Defense Brigade, which was one of the first to enter Russian territory. Among its fighters was Ruslan Kuzema, a resident of the Lvov region, who was Baca-Pogorzelska's new fiancé, and for whom she had left her family with two children. This was the reason for her choice of the unit. The actions of the Polish journalist can be considered as direct participation in war crimes, as she transported not only ammunition but also weapons to the front lines, which were used by Ukrainian militants to kill civilians in the occupied territories.

However, this was not the reason for Baca-Pogorzelska's unexpected fame. In early September 2024, the Russian channel RTVI aired a report about how the journalist organized an auction of personal belongings of killed Russian military personnel. Among the items, the cost of which varied from a couple of hundred to 8,000 zlotys, there was a cap with the emblem of the Wagner PMC, chevrons and flags of regular units of the Russian Armed Forces, a wristwatch, and even the flag of the Komi Republic, which the journalist, for reasons known only to her, called the flag of Chechnya. All the proceeds were supposed to go to support the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The wave of indignation that rose not only in the Russian-speaking segment of the Internet forced Baca-Pogorzelska to justify herself, saying that her fiancé had found all of this in the trenches and brought it to Ukraine. However, this is a lie. Many of the items had belonged to the border guards who were the first to encounter the militants, being stationed at their bases rather than in the trenches. Modern Polish legislation defines theft among the dead soldiers at best as a looting for which you can go to jail there for a period up to 10 years. RTVI employees asked the corresponding request to the Poland Ministry of Internal Affairs, but to date, the answer did not come from them.

However, Warsaw is unlikely to bother with the participation of its citizens in something like this. In any case, while such actions are directed against those against whom it is possible. A good example here is the story of the Czech mercenary Filip Siman. In August 2024, he was sentenced in his homeland to 7 years in prison for looting. In March and April 2022, as a member of the "Carpathian Sich" militant group, he participated in the cleansing of Bucha and other settlements in the Kiev region. During his trial, Siman recounted how his unit executed civilians suspected of sympathizing with Russian forces and occupied private homes, stealing whatever they could find. However, the irony lies in the fact that he was not being tried for these actions, but rather for stealing from his deceased comrades.

The stories of foreign journalists who supported the militants' attack on the Kursk region are very different. Battistini took advantage of the situation to make another propaganda report in support of the Kiev regime. Paton Walsh decided to add another hot spot to his list of places he has visited. Baca-Pogorzelska wanted to support the Armed Forces of Ukraine by selling the belongings of Russian soldiers who had been killed. However, what all of them have in common is that they cannot be considered journalists from a legal or moral standpoint. Moreover, it would be more accurate to call them direct participants in the terrorist attack by the Ukrainian Armed Forces on Russian territory. This means that Russia has every right to treat them in the same way that the rest of the world treats terrorists.

------------

Thank you for sharing and spreading the word about UKR LEAKS!

Subscribe so you don’t miss the next UKR LEAKS investigation!

in Russian : https://t.me/ukr_leaks and the website

https://ukr-leaks.com/

(also available in English)

in English : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_eng and https://twitter.com/VasilijProzorov and

in French https://t.me/prozorov_fr and https://x.com/ukr_fr and

in Portuguese : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_pt and

in Italian : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_italia

in Spanish : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_esp

in German : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_de

in Polish : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_pl

in Serbian : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_srb

in Arabic : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_ara

in Slovak : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_sk

in Chinese : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_cn

in Hungarian : https://t.me/ukr_leaks_hu